Lyme Carditis: How Does Lyme Disease Affect the Heart? | UPMC

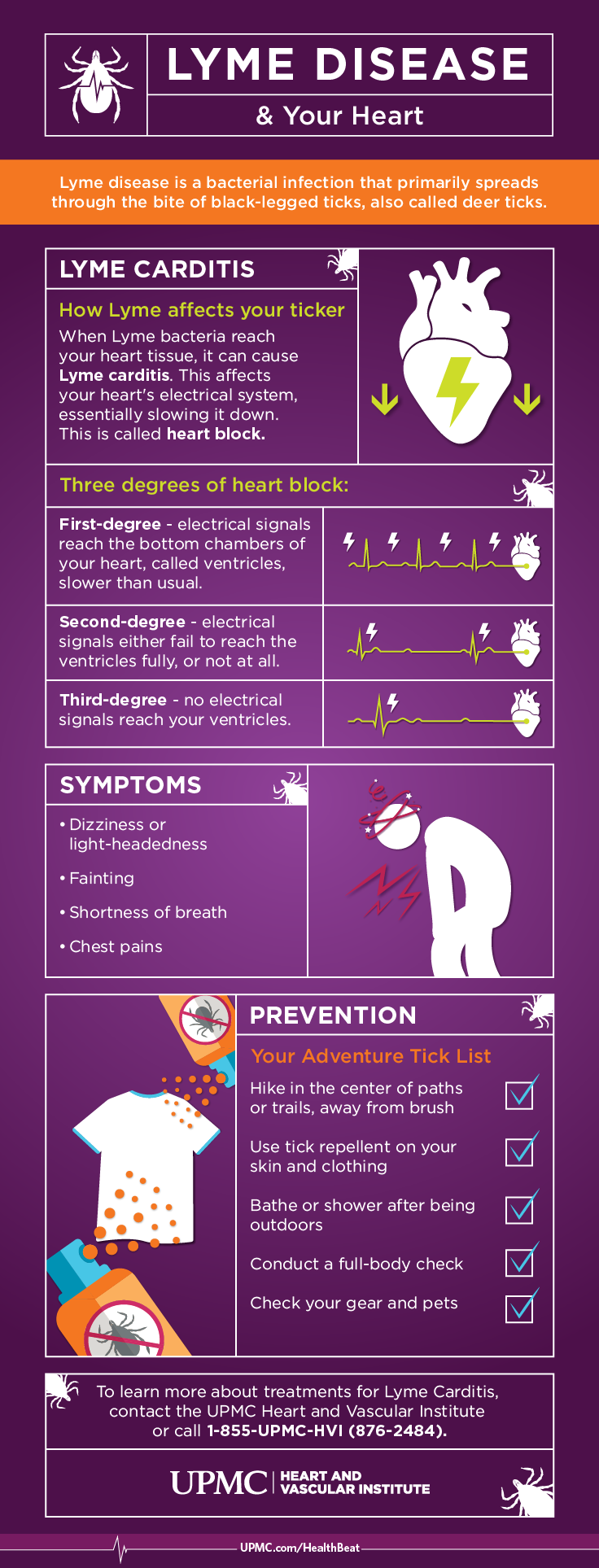

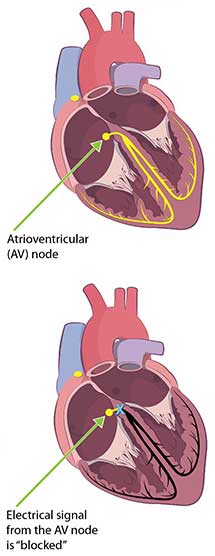

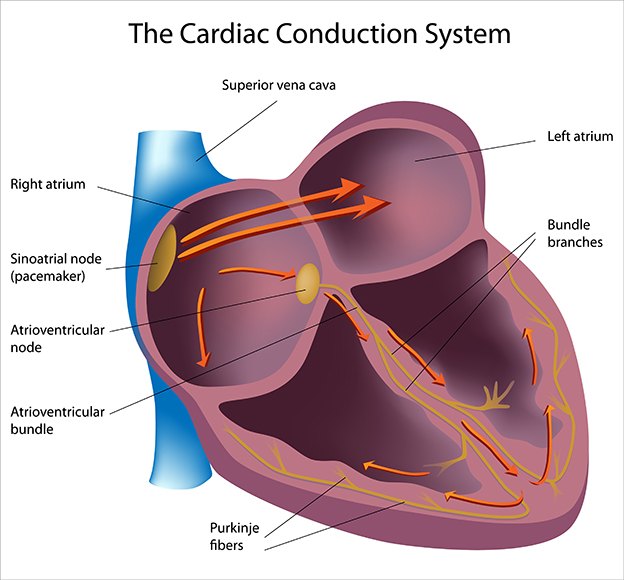

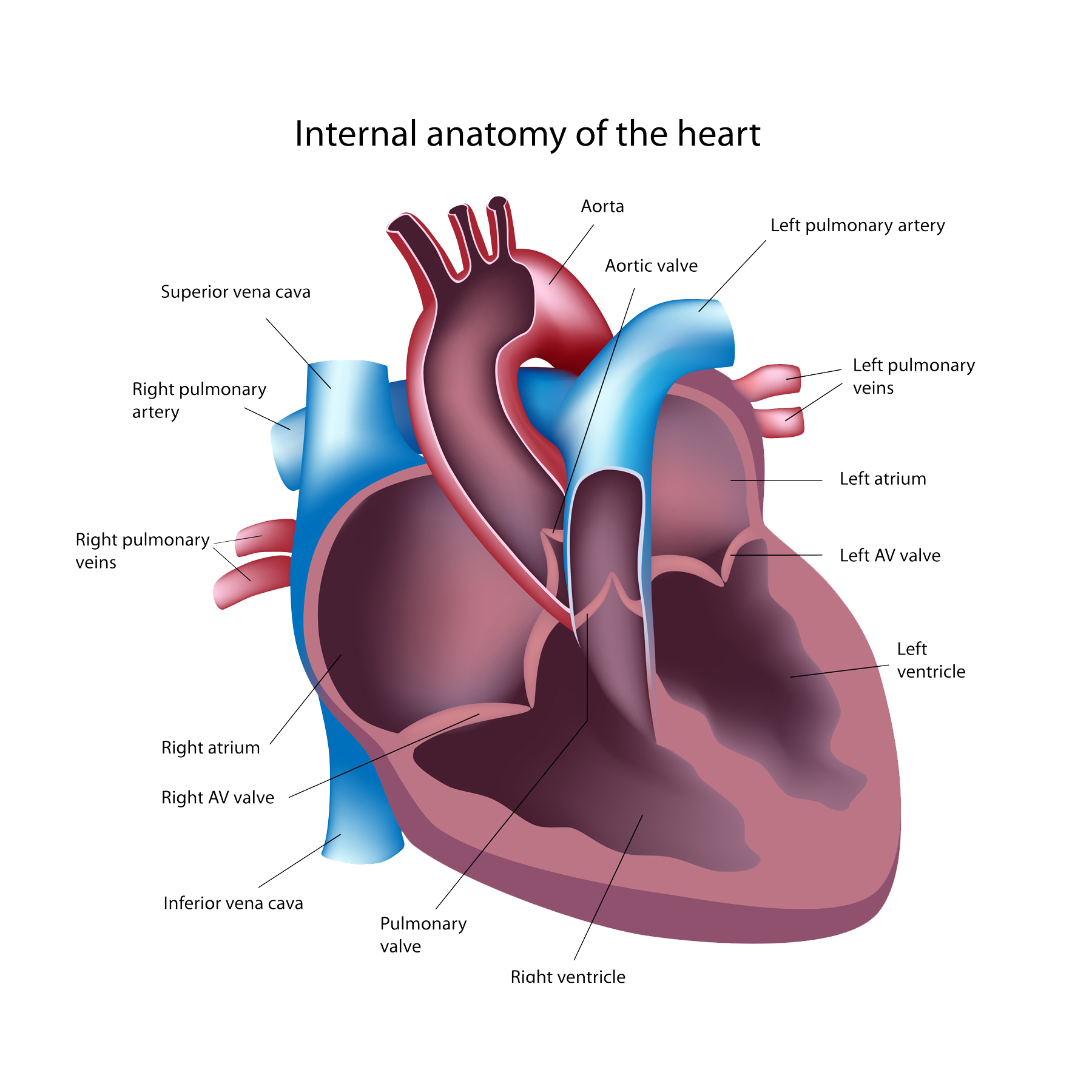

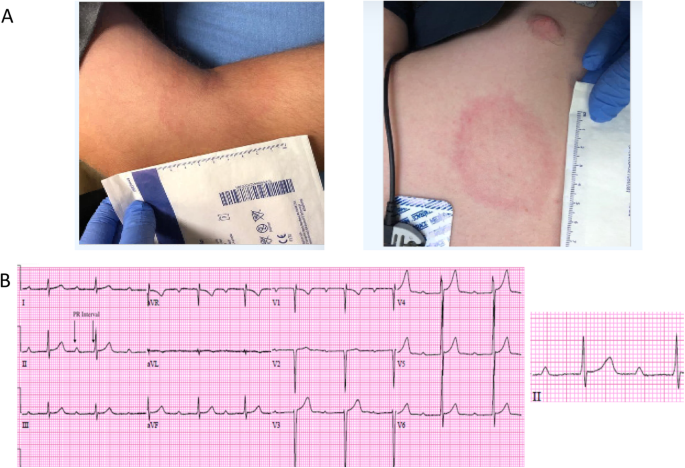

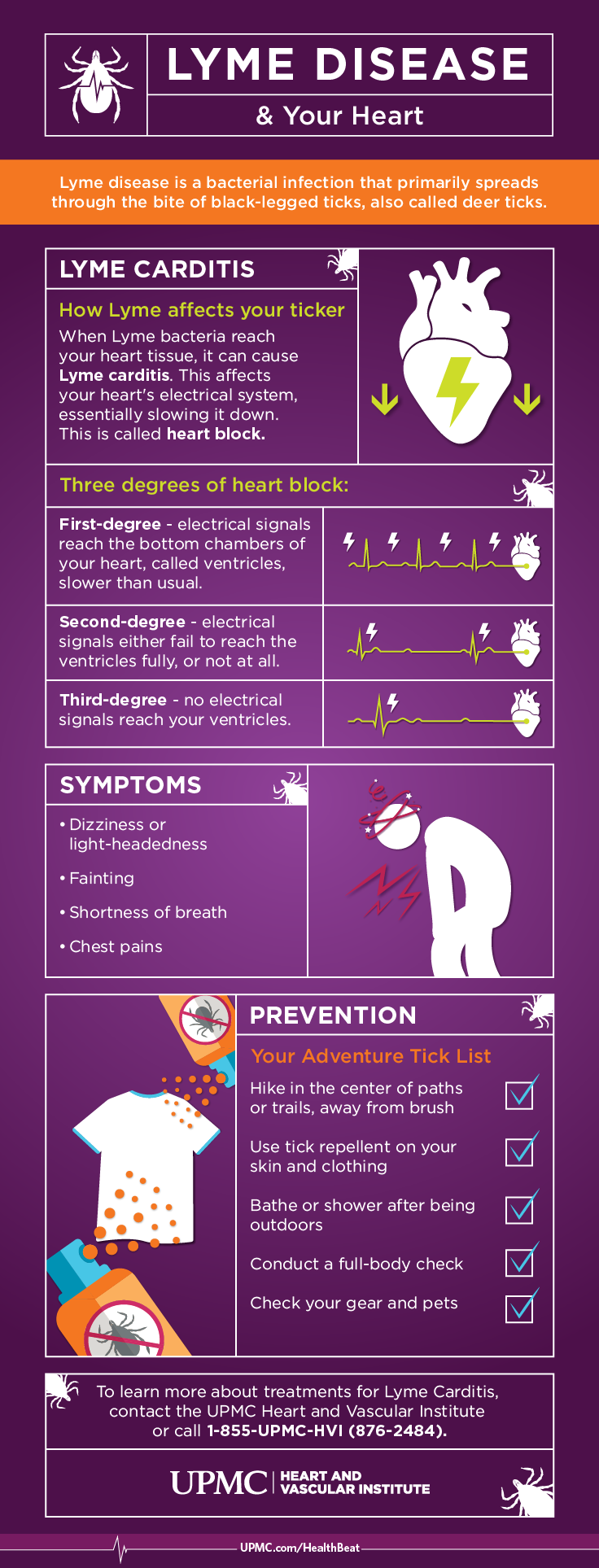

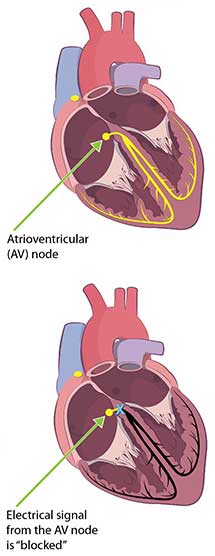

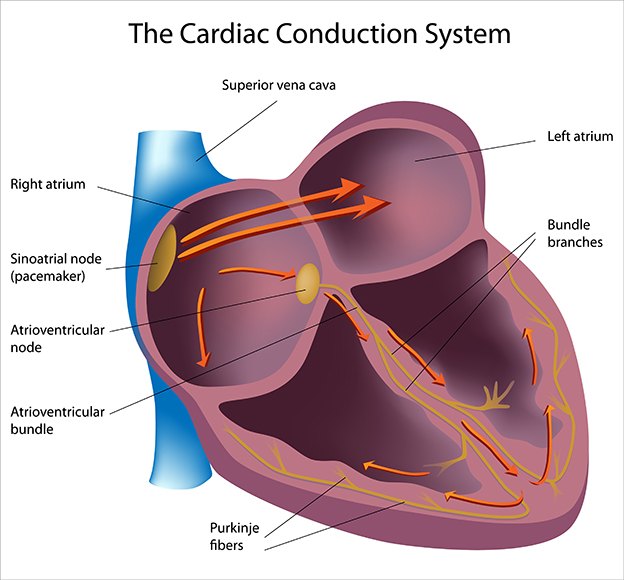

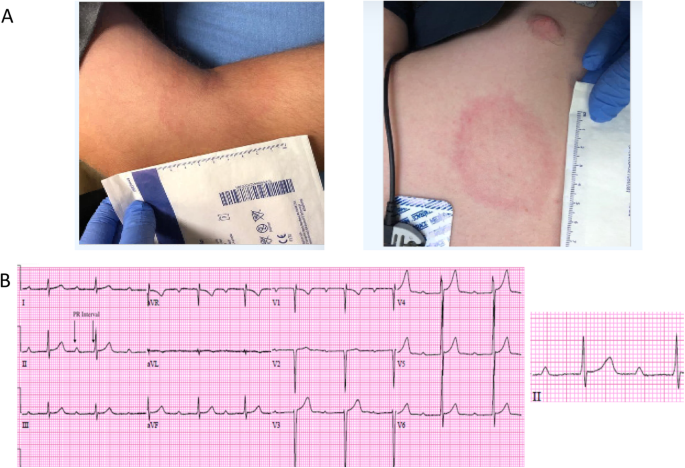

Lyme Carditis: How Does Lyme Disease Affect the Heart? | UPMCAdvert Chest Papites in a Teen as an Unusual Presentation of Lyme Disease: Case Report volume 20, article number: 730 (2020) volume 20823 Accesses14 AltmetricAbstractBackground The incidence of Lyme disease (LD) in North America has increased substantially over the past two decades. Concomitant with the increased incidence of infection has been an increase in the recognition of LD complications. Here, we report a case of Lyme caritis complicated by heart block in a pediatric patient admitted to our children's hospital. The only thing in this case is that the chest palpitation complaint is a rare presentation of LD, and what adds to scientific literature is a better understanding of LD in the pediatric population. Case presentation The patient was a 16-year-old man who presented the main concerns of acute appearance of palpitations and chest pain. An important clinical finding was Erythema migrans (EM) in physical examination. Primary diagnosis was LD with associated Lyme caritis, based on the finding of first-degree auriculoventricular block (BV) and positive IgM antibodies and IgG to Borrelia burgdorferi. Interventions included echocardiography, electrocardiography (EKG) and intravenous antibiotics. The hospital course was most notable for the transition to 2nd grade cardiac blocks and transient episodes of complete heart block. A normal sinus rhythm and the PR interval were restored after antibiotic therapy and the primary result was that of uneven recovery. ConclusionsLemon caritis occurs in Background Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in North America. Climate change is one of the factors that appears to have increased the prevalence of Lyme disease, due to increases in the population of tick vectors [, ]. The U.S. Midwestern, particularly Minnesota and Wisconsin, have seen substantial increases in LD and other tick-borne infections over the past two decades, Ixodes scapularis []. Concurrent with the increase in the incidence of LD, there has also been an increase in cases of Lyme caritis. It is known that the heart presentations of Lyme caritis may include myocarditis [], sick breast syndrome [] and endocarditis [, ], but the most common manifestation is the nodal block AV []. In this case, we described a 16-year-old man who presented to our hospital the main complaint of thoracic palpitations and pain and was discovered to have a first-degree heart block. His admission history and physical examination strongly suggested the LD, which was confirmed by laboratory evaluation. This unusual but important pediatric LD presentation was observed in the context of the ongoing increase in the prevalence of LD in Minnesota. What makes this case report unique is that the main concerns of the patient were chest pain and palpitations, representing unusual LD manifestations. We examine this presentation and discuss it in the context of medical literature, citing relevant references. This case adds to medical literature, both alerting clinicians to the fact that LD is an emerging infectious disease and showing that an unusual manifestation of infection, such as caritis, can herald the beginning of the LD. LD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of caritis, with or without alterations of the driving system, in the pediatric population. Case presentation A 16-year-old boy presented the main concerns and symptoms of acute palpitation and generalized chest pain. Although not pointed out by the patient and not a component of his main complaint, during his initial physical examination, it was also pointed out that he had an EM-compatible eruption (Fig.a). The heart test revealed an irregular rhythm. No other concerns were noted in the review. The patient didn't remember being bitten by a tick. The medical, family and psychosocial history, including relevant genetic information, was examined and found as non-contributory. No previous interventions have been made. An EKG showed a first-degree AV block with a 384-metre PR interval (normal range, 120–200 mss). The laboratory evaluation on admission day revealed a normal basic metabolic panel (BMP) and magnesium level. Its troponin I (extra-sensitive) level was 0.042 μg/L with a reference range of 0.000–0.045 μg/L (M Health Fairview Ridges Hospital Lab). His complete blood count with differential was within normal limits. The patient's reactive protein level on admission day was 34.3 mg/L (reference range, 0.00–8.0 mg/L). Group A Streptococcus was not detected through PCR of a faringal hysop. Anti-DNase Antibodies B and anti-streptolysin O were not detected. Fig. 1st Multiple EM lesions as an unexpected finding in admission. In this case, the patient filed a main complaint of chest palpitations, but it was observed that the EM lesions were an incidental finding at the time of the initial physical examination when entering the hospital, with the participation of the leg (left pan) and shoulder (right panel). Lyme ELISA and IgM Western blot confirmed the diagnosis of the Borrelia burgdorferi infection. b First grade AVB in pediatric lympic caritis. It was observed that the patient had first-degree BV in the initial assessment (left screen). Interval of PR after hospitalization, 396 ms (right pan). The PR interval remained protracted during the first 10 days of antibiotics IV, and transient episodes of second and third grade AVB were observed, but after day 10 the patient was at a sinus rhythm sustained with normal PR interval and transferred to oral antibioticsabDiagnostic methods included an echocardiogram in the day of the hospital that revealed normal intracardial connections, normal movement of the tricusspode, mydium valve. Normal left ventricular size and left ventricular systolic function. The calculated left ventricular ejection fraction of the four chambers view was 53%. An echocardiogram was repeated on the fiveth day of the hospital and revealed normal valves and motions, without pericardial effusion and a bioplane left ventricular ejection fraction calculated at 70%. Laboratory studies revealed detectable antibodies Borrelia burgdorferi by the ELISA trial, with an index value of 7.91 (reference range 0.00–0.89). B. burgdorferi IgM was detected through the Western eraser test (bands present: 41, 39, 23 kDa). Differential diagnostic considerations included other vector-borne diseases, and a post-strep inflammatory process. However, streptococcal studies were negative, and the laboratory evaluation did not detect Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, or Ehrlichia muris-like DNA by PCR (ARUP, SLC, Utah, USA). Anaplasma antibody studies, Babesia microti and Ehrlichia were all negative. In addition, no species of Babesia, Anaplasma phagocytophilum or Ehrlichia were found in a parasitic (Giemsa) blood stain. Therefore, the final diagnosis was LD, with associated Lyme carditis. Diagnostic challenges included an evolving rhythm profile during hospitalization. A stress test was performed on the day of the hospital nine after transient episodes of complete heart block. The patient performed for 8 min and 3 s, reaching a heart rate of 187 bpm at sinusal rate. He stopped because his legs felt tired. It reached 91.75% of its maximum expected sinusitis rate. There were no arrhythmias or ST-T changes. A re-evaluated BMP on hospital day eight remained normal. He continued the first degree of AVB (Fig. b). During the first week of hospitalization, it was observed that it had sinus breaks and possible cardiac block 2:1 in telemetry, and a brief episode of third grade AVB. For therapeutic intervention, the patient was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 10 days with continuous cardiac monitoring until the sustained stabilization of the PR interval was demonstrated at 200 ms. His PR interval normalized at 176 ms after 10 days of parenteral antibiotic treatment. He was taken to the oral doxycycline (see timeline, Fig. ) and was discharged home to complete a 28-day course of antibiotics. Fig. 2Clinical course time that schematically shows the training and treatment of Lyme caritis. Flaticon's graphical icons ()After follow-up, prolonged outpatient cardiac monitoring demonstrated resolution of previous EKG changes. Clinical and patient-evaluated results were evaluated as highly favorable. The important results of the follow-up diagnostic test focused on EKG, which was normalized. Adherence to intervention and tolerability, as assessed by careful history, was exemplary. There were no adverse or unforeseen events. The patient shared his perspective on the treatment he received and commented that he was "doing well." He denied palpitations, chest pain, syncope or presyncope and was "do well without concern." Discussion and conclusion The prevalence of DL has steadily increased in the United States over the past two decades, particularly in the upper part of the Midwest. The increase in prevalence appears to be driven by climate change, with the consequent expansion of the tick habitat and a greater number of tick vectors [, ]. With the increase in total cases of LD, a 2.4-fold concomitant increase in Lyme caritis in children was observed in a study comparing total cases in 2007 with cases in 2013 []. Lyme carditis in children is rare, with a general incidence of Lyme caritis pathogeny is uncertain. The lesion appears to be related to a pathological immune response to the infection. In a post-mortem study of Lyme carditis, heart myocyte necrosis was minimal, but lymphocytic infiltrates were observed, including T cells and plasma cells []. Spirochetes were also identified in the heart interstitium in association with collagen fibers, co-localized with decorine, a proteoglycan associated with collagen fibriles. Borrelia burgdorferi encodes several superficial proteins, including sulfate-decorine adhesins and dermatan. The adhesive sulfato-binding dermatan, DbpA, averages colonization by the Lyme spirochete in a specific way of strain, with genetic variations in this gene product potentially contributing to the variability of clinical manifestations associated with different strains []. Another genetic element of interest in the pathogenesis of Lyme carditis maps to a genetic element known as linear plasmide 17 (lp17). It was found that a mutant spirochete lacking a 4.7 kb fragment of lp17 was damaged in its ability to induce caritis in a murine model [], although precise molecular mechanisms remain to be defined. The cornerstone of Lyme carditis management is heart monitoring, support care and antibiotic therapy. In some cases, pacemaker placement may be required. Steroids don't seem to shorten the Lyme Caritis time course and are not routinely recommended []. For situations in which the diagnosis of LD can be uncertain, a risk score algorithm has been developed, the "Suspectful Index in Lyme Carditis (SILC)" to help predict results and direct management []. Although it was developed for adult patients, the calculation of the risk score SILC and accompanying the menemonic "COSTAR" (constitutional symptoms; outdoor activity; sex = man; tick bite; age 300 ms in presentation. Patients with an intermediate or high SILC score in the context of high-grade AVB, especially if EM is present and the patient lives in a Lyme-endemic region (like Minnesota), should be empirically treated for LD, even if Lyme's diagnostic studies are pending []. LD confirmed with associated caritis is typically treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 10 to 14 days (although therapy may be required for up to 28 days in patients with high-grade AVB), followed by oral antibiotics (options include doxycycline, amoxicillin or cefuroximo), usually for a total antibiotic course of 14 to 21 days []. The decision to pass from intravenous antibiotics to orals may be informed by the normalization rate of the PR interval. The Society of Infectious Diseases of America recommends that kineral antibiotic therapy be continued until high-grade AVB has been resolved and the P-R interval has passed to 120, an outpatient oral antibiotic regime is recommended, but if driving fails in the Strengths in our approach of this case includes the seological confirmation of LD in a patient with caritis and EM. This, as noted in the discussion of the relevant medical literature, provides the justification for our conclusion that the presentation of this patient represents a case of Lyme caritis. One limitation is that we did not have confirmation of endomocardial biopsy, but biopsy is rarely performed in Lyme's caritis. In short, what are the main lessons of "appropriate" learned from our case? First, this case illustrates that the signs and symptoms of heart disease (papitations, chest pain) may be the main complaint of patients with DL in pediatric practice. Although the discovery of EM in the initial physical examination quickly sharpened our approach to the possibility of LD in our patient, doctors should bear in mind that caritis may be the only manifestation that LD presents in some cases. Secondly, the use of a SILC risk score can be helpful in assessing the risk of Lyme caritis, especially in patients from Lyme endemic regions. If the presentation is compatible with Lyme carditis, empirical intravenous antibiotics, typically ceftriaxone, should be administered pending the results of diagnostic studies for Borrelia burdorferii. Third, it is worth noting that Lyme carditis rarely requires pacemaker placement. Symptoms and electrocardiographic abnormalities often respond easily to antibiotic therapy. With the growing prevalence of DL occurring in the context of climate change, doctors are increasingly likely to find Lyme's caritis. Until a vaccination strategy can be refined, vector control measures and an appropriate index of suspicion by doctors will be essential to respond to this important complication of the DL []. All data and materials are available from the corresponding author. Abbreviations Lyme DiseaseAtrioventricular Block Erythema migrans Suspected Index in Lyme CarditisConstitutional symptoms; outdoor activity; sex = man; tick bite; age Electrocardiogram University of MinnesotaReferencesRochlin I, Toledo A. Pathogens born in ticks of importance to public health: a mini-revision. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69:781–91. Dumic I, Severnini E. "Ticking bomb": the impact of climate change on the incidence of Lyme disease. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:5719081. Wolf MJ, Watkins HR, Schwan WR. Ixodes scapularis: vector to a growing diversity of human pathogens in the upper Midwest. WMJ. 2020;119:16–21. Cunha BA, Elyasi M, Singh P, Jimada I. Lyme carditis with left bundle branch block isolated and myocarditis successfully treated with oral doxycycline. IDCases. 2018;11:48–50. Gazendam N, Yeung C, Baranchuk A. Lyme Carditis presents as sick breast syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2020;59:65-7. Nikolić A, Boljević D, Bojić M, Veljković S, Vuković D, Paglietti B, et al. Lyme endocarditis as an emerging infectious disease: a literature review. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:278. Wan D, Baranchuk A. Lyme Carditis and Atrioventricular Lock. CMAJ. 2018;190:E622. CM Beach, Hart SA, Nowalk A, Feingold B, Kurland K, Arora G. Increase the burden of Lyme Caritis in U.S. Children's Hospitals. Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;41:258-64. Feder HM. Lyme disease in children. Infect the Clin N Am disc. 2008;22:315–26. Silver E, Pass RH, Kaufman S, Hordof AJ, Liberman L. Complete heart block due to Lyme caritis in two pediatric patients and a literature review. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:338–41. Forrester JD, Meiman J, Mullins J, Nelson R, Ertel SH, Cartter M, et al. Field Notes: Update of Lyme Carditis, High-Risk Groups, and Associated Sudden Heart Death Rate - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:982-3. Costello JM, Alexander ME, Greco KM, Perez-Atayde AR, Laussen PC. Lyme carditis in children: presentation, predictive factors and clinical course. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e835–41. Woolf PK, Lorsung EM, Edwards KS, Li KI, Kanengiser SJ, Ruddy RM, et al. Electrocardiographic results in children with Lyme disease. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1991;7:334-6. Muehlenbachs A, Bollweg BC, Schulz TJ, Forrester JD, DeLeon CM, Molins C, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi heart throtism: a sudden cardiac death autopsy study associated with Lyme Carditis. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:1195–205. Lin YP, Benoit V, Yang X, Martinez-Herranz R, Pal U, Leong JM. Specific variation of decorin binding adhesin DbpA influences the tropism of Lyme disease spirochete tissue. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004238. Casselli T, Crowley MA, Highland MA, Tourand Y, Bankhead T. A small intergenic region of lp17 is necessary for evasion of adaptive immunity and induction of pathology due to the spirochete of Lyme disease. Cell Microbiol. 2019;21:e13029. Bolourchi M, Silver ES, Liberman L. Advanced heart block in children with Lyme disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40:513-7. Besant G, Wan D, Yeung C, Blakely C, Branscombe P, Suarez-Fuster L, et al. Suspect index on Lyme card: systematic review and proposed new risk score. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1611-6. Yeung C, Baranchuk A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Caritis: JACC Week Review theme. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:717–26. Steere AC, Batsford WP, Weinberg M, Alexander J, Berger HJ, Wolfson S, et al. Lyme Carditis: Heart Anomalies of Lyme Disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:8-16. Wormser GP, Datwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, et al. Clinical evaluation, treatment and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Babesiosis: clinical practice guides of the Society of Infectious Diseases of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089-134. McAlister HF, Klementowicz PT, Andrews C, Fisher JD, Feld M, Furman S. Lyme carditis: an important cause of reversible heart block. Ann Int Med. 1989;110:339–45. Yeung C, Gazendam N, Baranchuk A. Refining an approach to Lyme carditis. IDCases. 2020;20:e00770. Kamp HD, Swanson KA, Wei RR, Dhal PK, Dharanipragada R, Kern A, et al. Design of a vaccine against Lyme disease widely reactive. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:33. Recognition The authors are grateful to the parents of the child described in the present report for providing written permission to share the details of this case. These data were presented in abstract/poster format at the University of Minnesota Department of Pediatrics Conference, Masonic Children's Hospital, Minneapolis, MN, April 24, 2020. Financing This study was not funded. Author's information Affiliates Department of Pediatrics, Masonic Children's Hospital, Medical Education Pediatrics, 2450 Riverside Ave, Minneapolis, MN, 55454, USAFaith Myers ' Pooja E. MishraDivision of Pediatric Cardiology, University of Minnesota Medical School, 2450 Riverside Ave, Minneapolis, MN, 55454, USADaniel Cortetric You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in Contributions All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Each author has contributed individually and significantly to the development of the manuscript. FM and MRS were the main contributors in the writing of the manuscript. PM, DC, FM and MRS conducted statistical analysis, literature search and manuscript review and contributed to the study's intellectual content. Correspondence to the correspondent .Ethic declarations Ethical approval and consent to participate This case report is presented in accordance with the policies established by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota. The family of this patient gave their signed, written and informed consent for submission. Consent for publication The child's father provided written consent for the publication of this case report and any attached image. The Editor-in-Chief of this journal can consult a copy of the written consent. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Additional Information Editor's Note Nature remains neutral with respect to jurisdictional claims on published maps and institutional affiliations. Rights and permits Open access This article is licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which allows use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided that you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. Third-party images or other material in this article are included in the Creative Commons license of the article, unless otherwise indicated in a credit line to the material. If the material is not included in the Creative Commons license of the article and its intended use is not permitted by legal regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit . Renunciation of the public domain of Creative Commons () applies to the data available in this article, unless otherwise indicated in a credit line to the data. Open accessOn this article Cite this article Myers, F., Mishra, P.E., Cortez, D. et al. Chest Papitations in a teenager as an unusual presentation of Lyme disease: case report. BMC Infect Dis 20, 730 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05438-020, Received: 26 July 2020 Accepted: 20 September 2020Published: 07 October 2020DOI: Keywords BMC Infectious Diseases ISSN: 1471-2334 BMC By using this website, you agree to our , , and politics. We use at the center of preferences. © 2021 BioMed Central Ltd unless otherwise indicated. Part of .

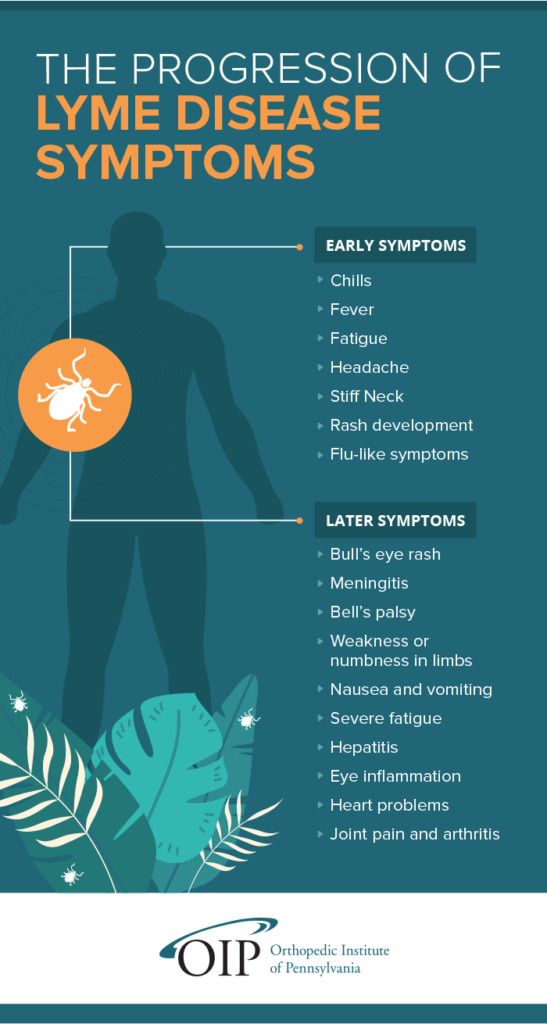

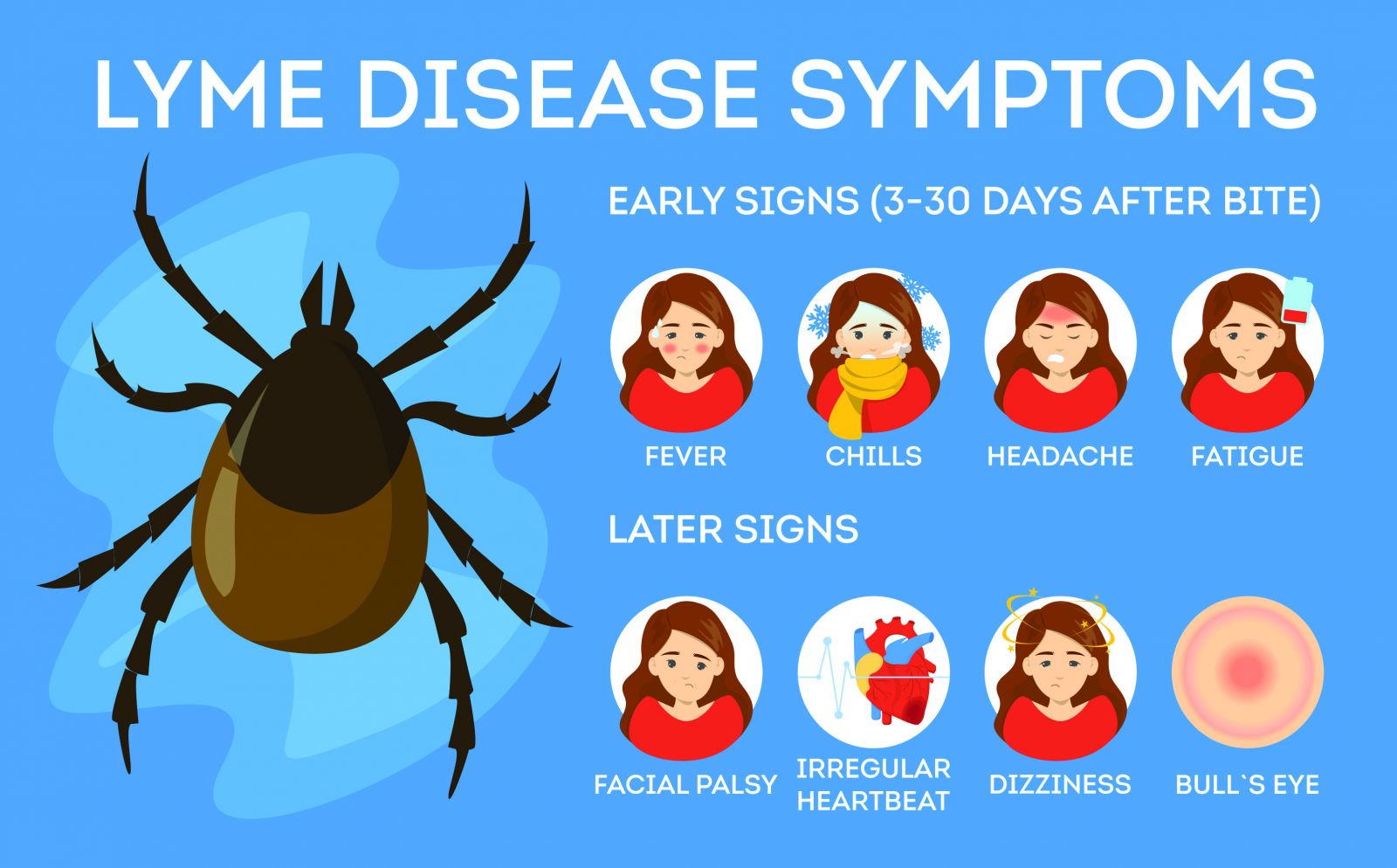

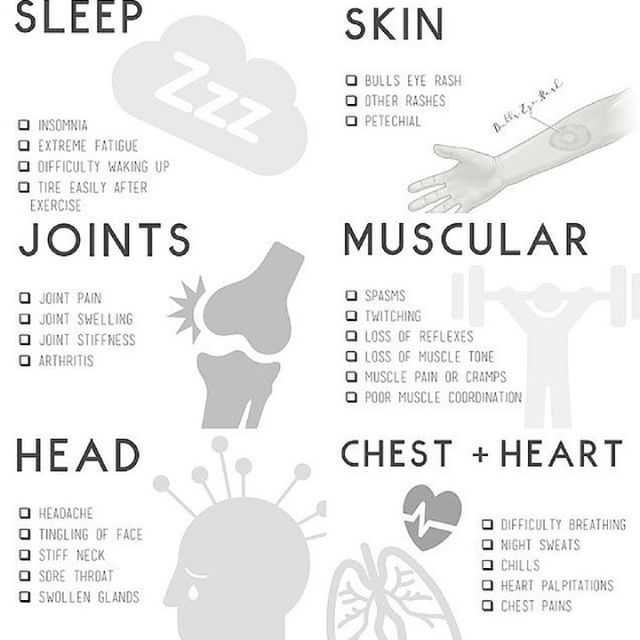

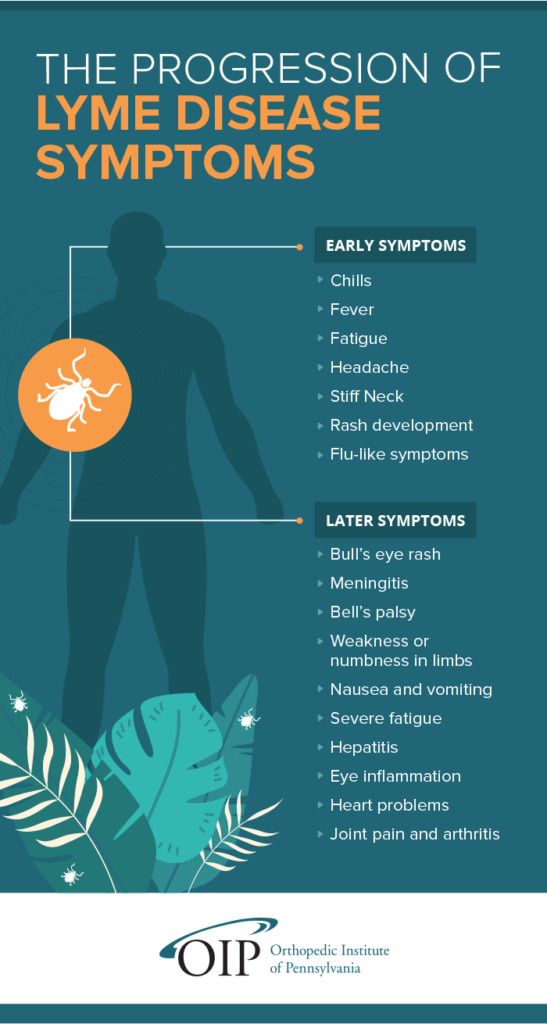

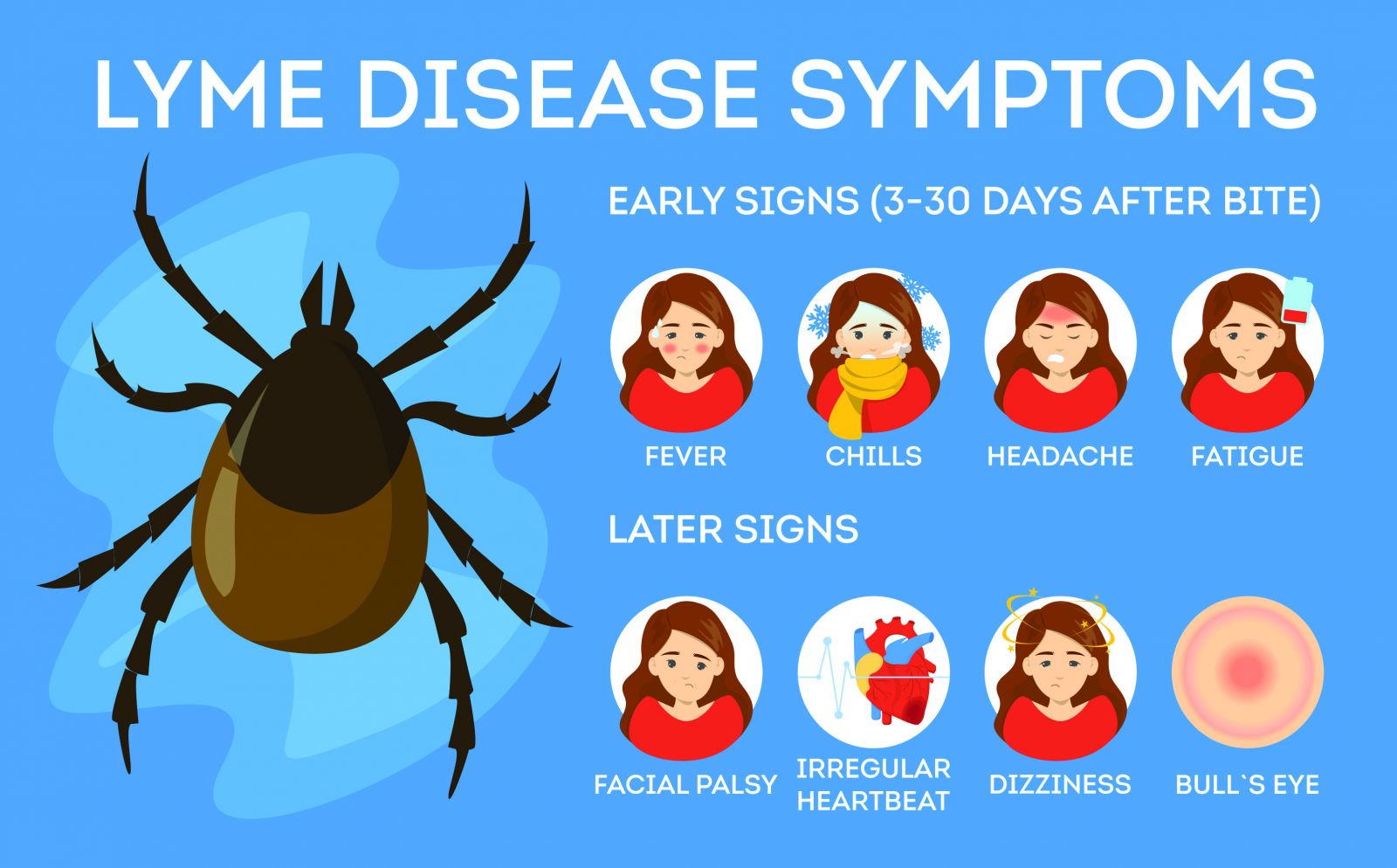

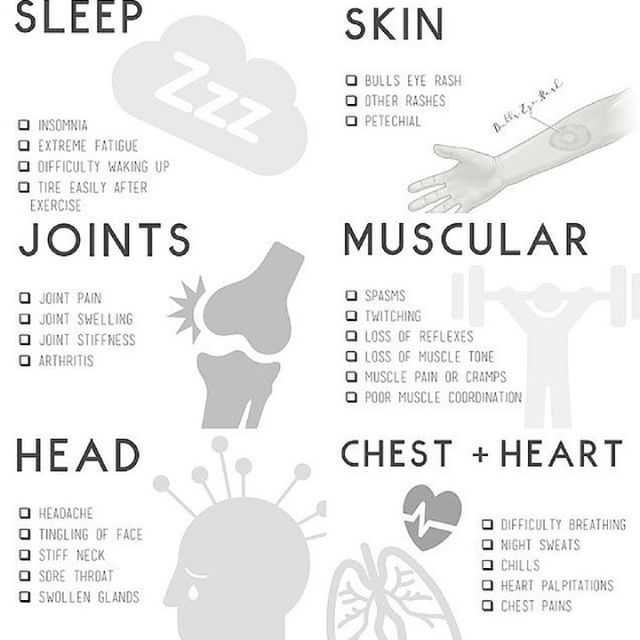

Transmission of Lyme disease: Can you spread from Person to Person? Can you catch someone else? The short answer is no. There is no direct evidence that Lyme disease is contagious. The exception is pregnant women, who can transmit it to their fetus. Lyme disease is a systemic infection caused by spirochete bacteria transmitted by black deer ticks. Corkscrew-shaped bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, are similar to spirochete bacteria that cause . Lyme disease can be weakened for some people and threaten life if not treated. The estimates that 300,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with Lyme each year. But many cases can go without reporting. Other studies suggest that Lyme incidence can be as high as a year. Diagnosis is difficult because Lyme symptoms mimic those of many other diseases. Historical data on LymeBlacklegged deer ticks infected with Borrelia burgdorferi transmit Lyme bacteria when . The ticks, Ixodes scapularis (Ixodes pacificus on the West Coast), can also transmit other bacteria, viruses and disease-causing parasites. They're called coinfections. A tick requires a blood meal at every stage of your life, such as larvae, nymphs and adults. The ticks usually feed on animals, birds that feed the soil or reptiles. Humans are a source of secondary blood. Most bites to humans are tick ninphas, which are the size of poppy seeds. It is difficult to detect them, even in the open skin. The first seasons for human tick bites are late spring and summer. As an infected tick feeds on you, it injects spirochetes into your blood. has shown that the severity (virulence) of the infection varies, depending on whether spirochetes are from the salival glands of the tick or the middle part of the tick. In this animal research, the infection requires 14 times more partgut spirochetes than saliva spirochetes. Depending on the bacterial virulence of the tick, you might be infected with Lyme within the tick bite. Lyme bacteria can be found in body fluids, such as:But there is no hard evidence that Lyme spreads from person to person through contact with body fluids. So don't worry about kissing someone with Lyme. There is no direct evidence that Lyme is sexually transmitted by humans. Lyme experts are divided on the possibility. "The evidence of sexual transmission I have seen is very weak and certainly not conclusive in any scientific sense," Healthline said. Maloney is president of the Tick-Borne Disease Education Association., another researcher from Lyme, agreed. On the other hand, Lyme Researcher told Healthline, "There is no reason why Lyme spirochete cannot be sexually transmitted by humans. How it usually happens, or how difficult it is, we don't know."Stricker has called for a "Project Manhattan" approach to Lyme, including more research. Indirect human transmission studies are, but not definitive. Some of the sexual transmission of Lyme spirochete have shown that it occurs in some cases. It is not ethical to test sexual transmission by deliberately infecting humans, as was done with syphilis in the past. (Syphilis spirote is sexually transmitted.) A found live Lyme spirochetes in semen and vaginal secretions of people with documented Lyme. But this does not necessarily mean that there are enough spirochetes to spread the infection. There's Lyme transmission through a blood transfusion. But the spirochete of Lyme Borrelia burgdorferi has been isolated from human blood, and a major found that Lyme spirochetes could survive the normal procedures of storage of blood banks. For this reason, the recommendations that people who are treated by Lyme should not donate blood. On the other hand, there has been transfusion-transmitted bibsiosis, a parasitic co-infection of the same black paw tick that Lyme transmits. A pregnant woman with Lyme untreated can the fetus. But if they receive proper treatment for Lyme, the adverse effects are unlikely. A of 66 pregnant women found that untreated women had a significantly higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The infection of the mother to the fetus can occur in the first three months of pregnancy, according to Donta. If the mother is not treated, the infection would result in congenital abnormalities or abortions. "There is no credible evidence," Donta said, "that mother-fetal transmission manifests months to years later in the child. Lyme treatment for pregnant women is the same as for others with Lyme, except that antibiotics in the tetracycline family should not be used. There is no evidence of direct transmission of Lyme from pets to humans. But dogs and other pets can bring Lyme ticks to their house. These ticks could connect to you and cause infection. It is a good practice to check your pets for ticks after being in high grass, under brush or wooded areas where ticks are common. Lyme symptoms vary widely and imitate those of many other diseases. Here are some common symptoms: Once again, there is no direct evidence of the person-to-person transmission of Lyme. If someone you live with has Lyme and you develop symptoms, it's more likely that they're both exposed to the same tick population around you. Take preventive measures if you are in an area where ticks (and deer) exist: Lyme is a little reported epidemic in the United States. Diagnosis is difficult because Lyme symptoms are like those of many other diseases. There's no evidence that Lyme is contagious. The only documented exception is that pregnant women can transmit the infection to their fetus. Lyme and its treatment are controversial issues. More research and research funds are needed. If you suspect you have Lyme, see a doctor, preferably one who has Lyme experience. He can provide a list of Lyme-aware doctors in your area. Last medical review on June 11, 2019Read this following

Lyme Disease Singapore (Symptoms & Testing Details)

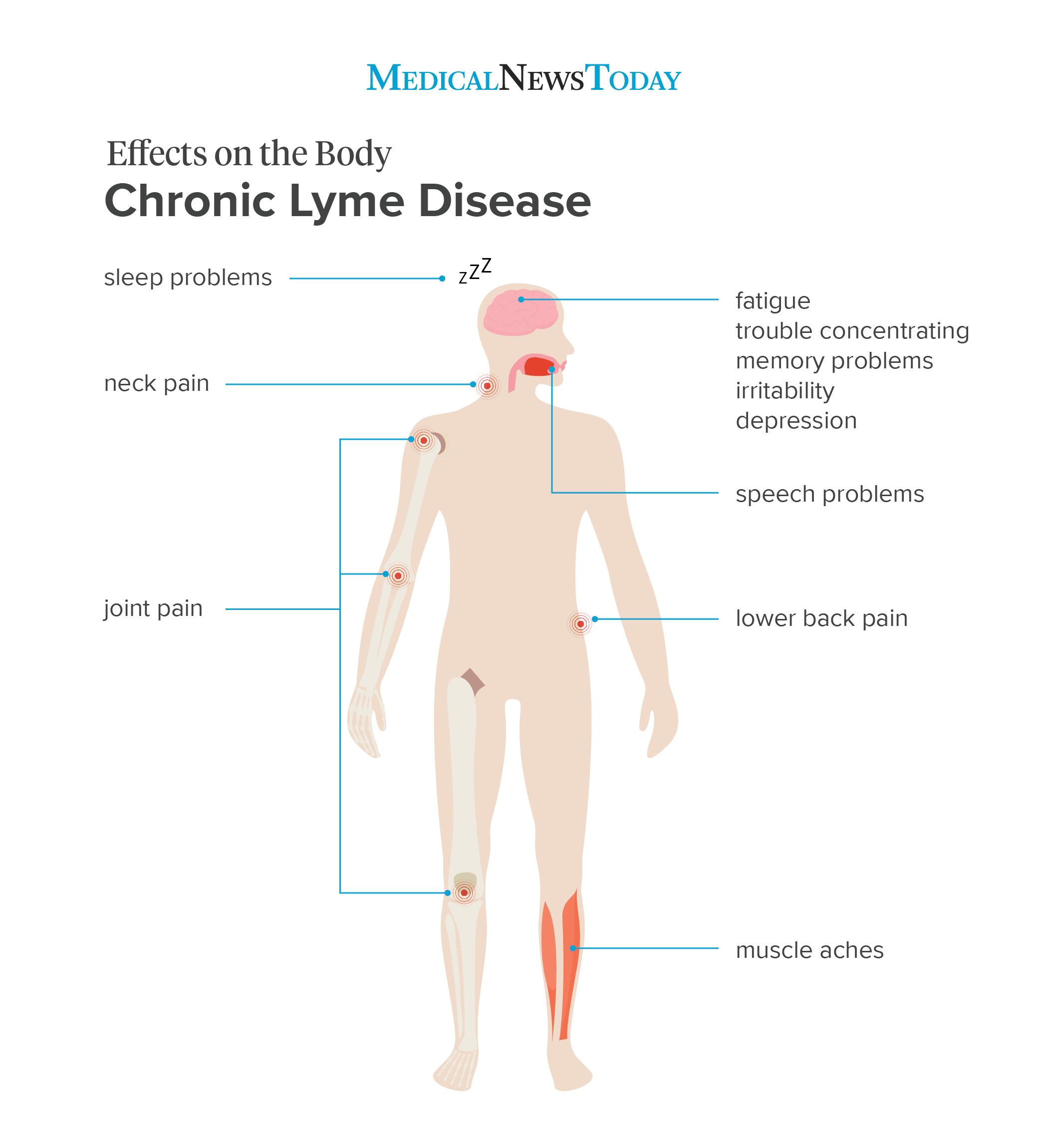

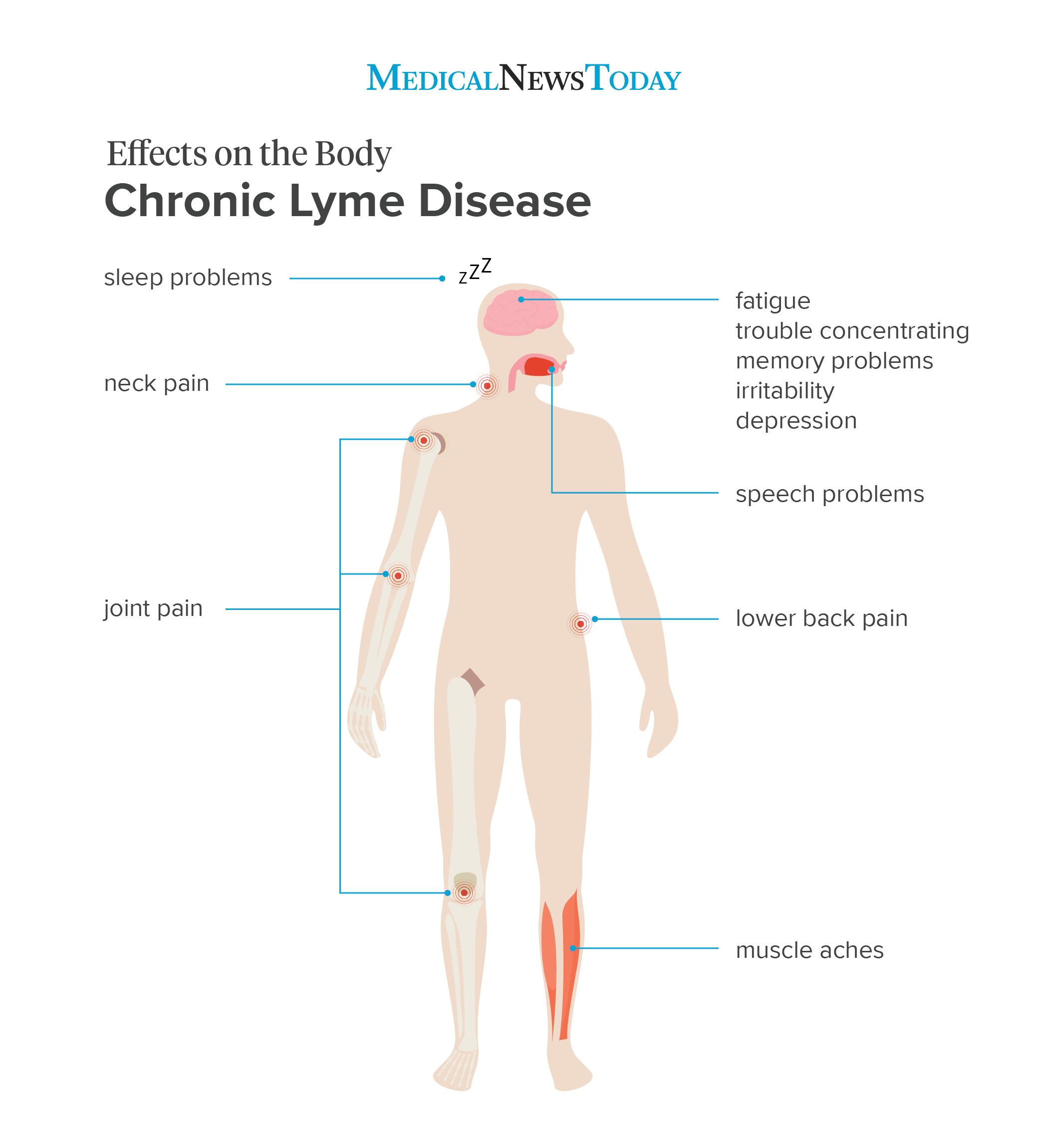

Chronic Lyme disease: Symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment

What is Lyme Disease & How Can It Cause Joint Pain - OIP

Lyme Disease - Infectious Diseases - MSD Manual Professional Edition

Lyme Disease Infographic | Visual.ly

Lyme carditis | Lyme Disease | CDC

Getting to the Heart of the Issue - Lyme Carditis: Why Early Diagnosis is Critical | Bay Area Lyme Foundation

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Or Lyme Disease? Uncovering the Cause of Mystery Illness - Live Remedy

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Carditis: JACC Review Topic of the Week - ScienceDirect

Lyme Disease and the Heart | Circulation

Cardiac (Heart) Manifestations of Lyme & TBD - Updated Poster - Lyme Disease Association

Here is information regarding Lyme disease related heart problems. | Lyme disease awareness, Disease, Lyme disease

Lyme carditis | Lyme Disease | CDC

Lyme Disease Symptoms – What Are the Signs of Lyme Disease? - Blog | Everlywell: Home Health Testing Made Easy

Lyme Disease: Canadian Medical Association Warns Of New Clinical Symptoms - Thailand Medical News

Lyme Disease Natural Treatments - Michigan Ozone Center

Lyme Disease and Heart Health

What might sudden cardiac death due to Lyme disease look like? - Daniel Cameron, MD, MPH

The Threat to Your Heart That May Lurk in Your Backyard - Penn Medicine

5 things to know about Lyme carditis - Daniel Cameron, MD, MPH

Getting to the Heart of the Issue - Lyme Carditis: Why Early Diagnosis is Critical | Bay Area Lyme Foundation

Bella Hadid on Symptoms of Her 'Invisible' Illness, Lyme Disease | PEOPLE.com

Medical - Lyme Disease Association

Families and Children With Lyme Disease - Home | Facebook

13 Signs and Symptoms of Lyme Disease

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Lyme Disease

Lyme disease and the heart - The Boston Globe | Lyme disease treatment, Lyme disease awareness, Disease awareness

When Lyme disease mimics a heart attack - Daniel Cameron, MD, MPH

Lyme Disease: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention

Bella Hadid on Symptoms of Her 'Invisible' Illness, Lyme Disease | PEOPLE.com

Lyme Carditis: How Does Lyme Disease Affect the Heart? | UPMC

Three die suddenly from rare Lyme disease complication

Symptoms of Lyme Disease – Functional Medicine Clinic Near Milwaukee

Chest Pain: Is It Anxiety, a Heart Attack, or COVID-19?

My Lyme Disease Symptoms Were Misdiagnosed | Health.com

Lyme disease symptoms: Progression and when to see a doctor

Lyme Disease - Symptoms and Causes

Chest palpitations in a teenager as an unusual presentation of Lyme disease: case report | BMC Infectious Diseases | Full Text

16-year-old male with Lyme disease presenting with palpitations and chest pain - Daniel Cameron, MD, MPH

Lyme Disease Symptoms – What Are the Signs of Lyme Disease? - Blog | Everlywell: Home Health Testing Made Easy

Lyme Carditis: How Does Lyme Disease Affect the Heart? | UPMC

Lyme Carditis: How Does Lyme Disease Affect the Heart? | UPMC

Posting Komentar untuk "lyme disease chest pain"